Photographed by Joshua Aronson

“I got this jacket at Tokio 7, a designer consignment shop on 7th Street and 1st Avenue when I used to live in that area of New York. I would also go and try and find some cheaper upcoming designers. But I never really found anything until this gem of a jacket by an old French designer, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac. Someone told me he doesn’t make clothes anymore. I love that. I love the jacket’s playfulness, and its ability to put me at ease.”

Tyler Mitchell, photographer

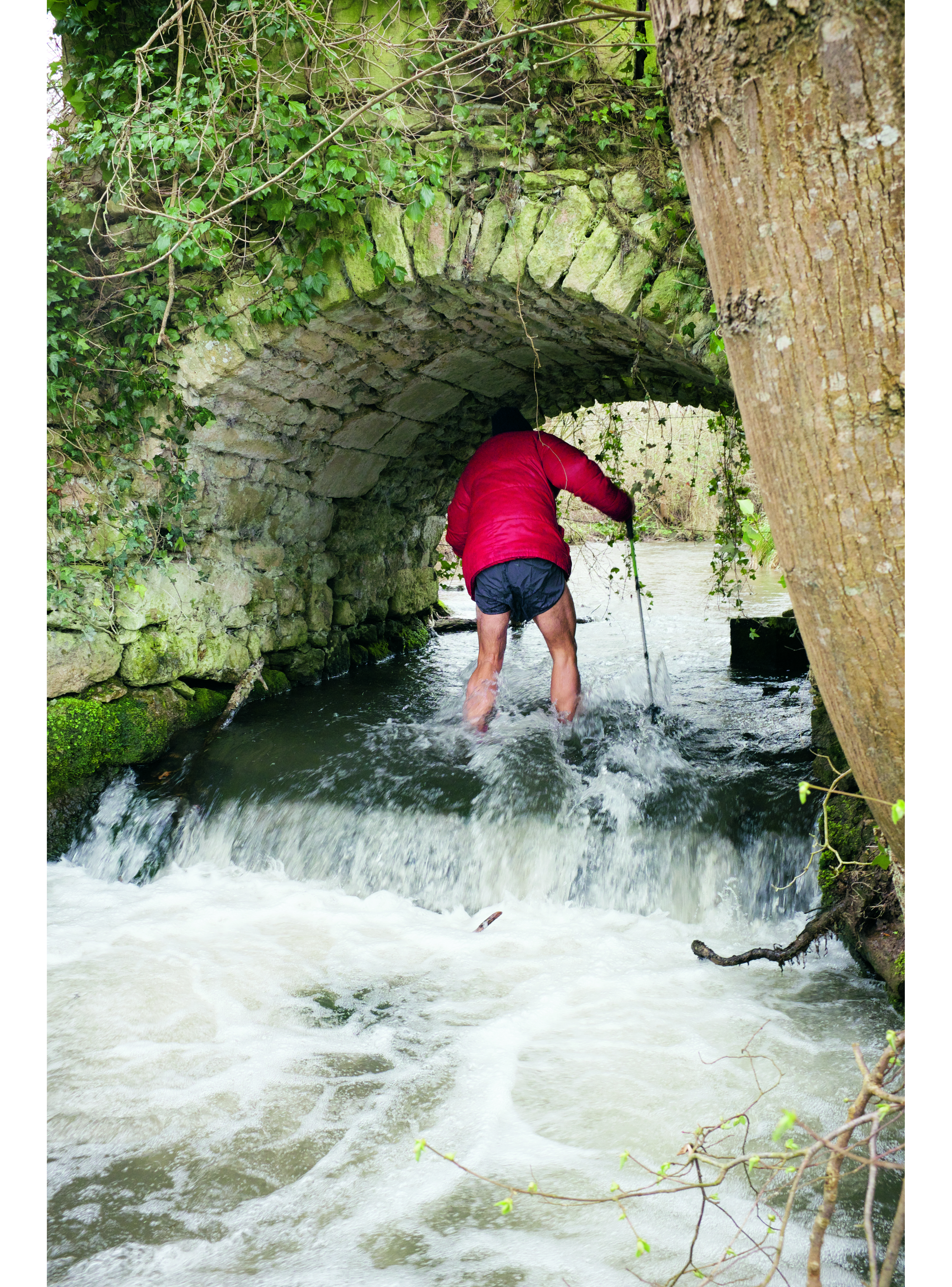

Kanye, Juergen & Kim, No.6, Château d’Ambleville, 2015. Photographed by Juergen Teller

“I have worn these shorts for over 10 years.

They are comfortable and they suit me.”Juergen Teller, photographer

Here’s a few things I’ve realised about clothes

1) Most fashion writing is about clothing up until the point of production. By this, I mean the clothes being written about are usually samples, of which there’s one version, in model size. It’s especially true of fashion-show criticism, but often fashion journalism is about clothing that has not yet entered a store. It’s rare that the writer will have actually worn the clothes for themselves.

2) Fashion writing often compensates for this lack of personal knowledge about the garment itself by resorting to clichés: “must-have”, “cult item”, “to die for”.

3) This language has no connection to how I feel about the clothing that I own, and which I enjoy wearing often. This is particularly true of fashion items which, when first shown on the catwalk, could have been subject of the hyperventilating language of garments not yet available to purchase.

4) I’m thinking in particular of a Prada knit cardigan, which was first shown on the autumn/winter 2016 men’s catwalk. It’s a chunky hand-knit constructed from scallop shapes in various colours, trimmed in red and fastened with a zip. I reviewed the show for the Financial Times, and wrote the following about the cardigan: “It was an immediate and obvious winner.”

6) I never think of it as “an immediate and obvious winner”. My thoughts about the cardigan don’t usually come in the form of words, but are more feelings of love and pleasure. These feelings are connected to the life already lived in it, and also the happiness that its colours, its heft, continues to bring.

7) My thoughts about the cardigan that come in the form of words are usually pretty mundane: “It’s still not been eaten by moths”; “It’s still not come unravelled”. These mundane thoughts are also thoughts of love.

Left: Clara’s mother, photographed by Julie Weisz. Right: Clara, photographed by Max Farago

“Sonia Rykiel never knew that this dress was going to travel to Argentina and be worn by my beautiful mother while she was pregnant with me. She didn’t know either that 30 years later I was going to wear it while pregnant with my own daughter, Alma. This year my mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and after a big fight she finished her treatment and is well now. ‘You give my clothes another life,’ she always tells me when she sees me wearing one of her pieces. Giving another life to an object, to a human and to oneself.”

Clara Cullen, filmmaker

Photographed by Michael James Fox

“I designed this top by way of scissors, stickers and my mum’s scanner when I was 15, creating the first ever piece for my own label Thames. It was during the 2012 Olympics, when the Brits held high hopes for Beth Tweddle (the pictured gymnast) to bring home the gold. The Evening Standard printed this rather unflattering photo of her when she disappointed, which was, to my twisted teenaged mind, a snide revenge. I cut the photo out, scanned it, Warholed it on my mum’s Dell to make the print. The neck label is a plaque that reads ‘Our Father Thames, a devoted parent who is never too old for work!’ but, being lexdyslic, what it really says to me is ‘Captain Shitacular is raising shit in Sunnyvale!’”

Blondey McCoy, skateboarder and designer

8) It’s clear to me the language of clothing after the point of production is very different from that before. We talk about, and think about, the clothes we wear in a different way from the clothes that have just been revealed somewhere in the world on a catwalk.

9) Why does this language feel less cultivated, less explored than the language before the point of production?

10) It’s certainly less glamorous. I’m writing this in one of my favourite old John Smedley sweaters. It’s navy, crewneck, of extra- fine Merino wool. There is a hole in the right cuff, and my thumb is lodged through it. The cuff has become like a fingerless glove. My thumb goes in the hole without thinking about it. My hand is seeking comfort. My body is reacting to the garment in ways that are different from the thought process that engages with clothes not yet worn.

11) And yet, because such reactions to worn clothing are instinctive, these instincts often go unnoticed, even if they are telling us about our relationship with clothing. It’s these sort of instincts that are drowned out by the noisy and perpetually unfullfiled desires of the consumer’s mind.

12) Our life in clothes isn’t the imagined world of the pieces we see on the catwalk, the imagined world where we feel connected to a brand because we fantasise a piece will be ours. That piece may well never even make it to stores, and when it does, in reality we have a mortgage to pay, a life to live. The language of fashion is often about this fantasy: what we might have, rather than what we actually own.

13) Our real life in clothes is very different. It might actually be more interesting. But it is also very individual, rather than a mass assumption about desire. It’s pretty useless for the fashion industry, which relies on the language of desire to make us buy more stuff.

Photographed by Chad Moore

“This silk camisole was a gift from Nicholas Ghesquiere when he was first with Balenciaga. I wore it to a dinner party in Paris with a photographer friend and my love. My friend had spaghetti; as he laughed, a speck of his red sauce spewed across the front. I was mortified… But as I began blotting the sauce from the silk, I realised it was the night to enjoy the garment: if it were ruined, so be it. I was lucky to have the damn thing on in the first place! The many other times that I wore it, traipsing around the world with my love and this gorgeous, handmade piece of heaven, were some of the best times of my life. Being in love, skipping the light fantastic with this spaghetti-strapped luxe silk cream beauty, I felt feminine, raw, beautiful. Since losing the love of my life, I hang it on my wall as if it were a photograph of times of my youth: young, wild, madly in love, and free.”

Cat Power, musician

Photographed by Tom Johnson

“In 1984, I got invited to a cocktail party with Margaret Thatcher, who I couldn’t stand. I wore my ‘58 Percent Don’t Want Pershing’ T-shirt under my office clothes and flashed it at the cameras as I was shaking her hand. Pershing missiles were a contentious political issue at the time and the photos went global. The ‘Choose Life’ T-shirt was the very first one that I did using the big lettering. I did a slew of ones like it, including ‘Use a Condom’, which Naomi Campbell wore on the catwalk. They were regarded as transgressional, but I didn’t have investors telling me not to ruffle people’s feathers or do things like our ‘Jail Tony’ T-shirt, for the illegal invasion of Iraq. That one got us into trouble!”

Katharine Hamnett, designer

14) It might also be that the way we talk about our real life in clothes is yet to be fully evolved.

15) It’s easy to assume that things are as they always were, but we’re actually at a very new point in our relationship with clothing.

16) Read a novel set in the 1920s – maybe book one of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time – to put this change of relationship in context. The way the characters talk about clothing, how we are told they feel about clothing, is completely alien to me.

17) In fact, I’d say read 1980s novels, too. The obsession over clothing in American Psycho is more hilarious, and more terrifying, than ever. It’s also completely particular to its time.

18) Clothing has really only recently been seen to be liberated. I’m 45, and it feels that within my lifetime individuals have felt they have meaningful choice and control of what they wear, away from uniform or social conventions. We have more chance, more often to wear clothing that we actually want to wear, rather than what we are told to wear.

19) But because we are always buying more clothes, our desiring mind often focuses on thinking about what we don’t have, than what we do.

“I am trying out wearing colours again, so I am dressed in a neon-green jumper, with an Acne jacket, my four-year-old jeans and cuban-heeled boots. I have held on to them every winter, as it makes life easier when getting around.”

Ib Kamara, stylist

Photographed by Anders Edström

“This is a Chanel couture suit from around 1965, made in the Mademoiselle Chanel era. I bought it 10 years ago and wore it a lot. I wear it a bit less now, because I feel I look old in it. I loved the fact the fabric was quite anti-bling, but with precious buttons. After buying it, I also discovered that it has a special Legion d’Honneur embroidery on it: a fine red thread discreetly sewn on the left side, for people who don’t want to wear the real thing (quite understandable). It is like using counterfeit money: that embroidery is intended for heroes and heroines of some sort. Very few women were on the list of Legion d’Honneur, so this suit is very special to me. I dream of finding out who owned this suit; I just hope her presence is protecting me and giving me strength.”

Camille Bidault-Waddington, stylist

20) This year, I’ve stopped buying so much clothing. There are practical reasons – I have no wardrobe space left – but also I wanted to see what it was like to concentrate on clothing I already own.

21) It’s been really fun.

22) What’s most satisfying is the removal of the anxious need to buy something – anything. Removing that anxious need allows me to think more clearly about my feelings for what I already own, and the stories that garments tell about my life, the way that I live.

23) It makes me want to know more about the clothing owned by others, what stories those garments tell about their lives, the way they live.

24) I still buy fashion when I feel a certain connection to it: jackets and knits by Craig Green; an Undercover zip-up with imagery from 2001: A Space Odyssey; a sweatshirt by Cactus Plant Flea Market; bootleg T-shirts by Boot Boyz Biz.

25) But I’ve found more I’m drawn to pieces that I know will have longevity: a worker’s jacket in egg blue thick cotton by Le Mont Saint Michel; a red sailor smock by Saint James, bought from Arthur Beale in Covent Garden. My jeans are made by Blackhorse Lane Ateliers for Labour & Wait.

26) I’ve written this piece as numbered points on purpose. It feels a clean way to investigate this thinking. I wanted to avoid the sentiment of nostalgia, which is how fashion writers often talk about much-worn clothes. I think our relationship with these clothes can be alive and vital, rather than cast as a relic of halcyon days. I wanted to construct these thoughts away from the fog of much fashion writing. I include my own fashion writing within this fog – a fog from which I would like to walk free.