Photographed by Jamie Hawkesworth. Romania, 2018

Incredulity, outrage, anxiety: these emotions tumbled through my brain as I watched the news reports this year about the catastrophic fires engulfing the Amazon rainforest. The immediate effects were clear – charred tree stumps, scorched earth and a thick pall of smoke darkening the sky and polluting the atmosphere. The long-term consequences for the region’s biodiversity, inhabitants and the climate have yet to be calculated. Forest fires are one among many disasters that we face as global temperatures rise. Throughout the world drought is exacerbating the fires that occur naturally in the dry season, but in Brazil, parts of the forest were deliberately torched to signif y support for president Jair Bolsonaro’s economic policy of deforestation for agriculture and mining.

We humans have a chequered relationship with nature. Most of us would agree it is important to us. We feel refreshed and alive when we interact with nature, whether tending a potted plant, turning out for a bracing walk or watching the clouds drift by on a still summer day. Natural history fascinates and delights us, but we are only just beginning to grapple seriously with the crisis enveloping the earth and its ecosystems following centuries of degradation caused by human activity. Most of us lead essentially indoor, urban existences and we like our lives to be comfortable, clean and convenient. We have grown used to a world of choice, plenty and instant gratification at the click of a mouse. Our relationship with nature is skewed: we engage with it on our terms and to fit our agenda.

Photographed by Angelo Pennetta. Styling by Claudia Sinclair

“I’ve always had a deep love and appreciation for the sea and been obsessed by sharks for as long as I can remember. Ever since I first learned about the practice of hunting sharks for their fins, I have tried my best to help the ocean and minimise the devastation we wreak on delicate marine ecosystems. I worked for just over a year at an ocean-protection organisation called Project 0, which does great work trying to create new revenue streams for aquatic conservation projects around the world. On a personal level, there are many things you can do to help. Always using reef-safe sunscreen is a small but important lifestyle change. The biggest threat facing the oceans is overfishing, so making sure you know exactly where your fish is coming from is vital. Ensure that it was legally caught, not fished from a marine protected area and not caught by an industrial fishing net. Going vegan, of course, really helps with this too. On top of this, we kill 100 million sharks a year; their meat is used in many things, including beauty products, so make sure to check for shark in everything you buy. It will be labeled as squalene: keep an eye out for it! My love for nature made me feel a part of something in a time in my life when I felt incredibly disconnected from the world. The ocean reminds me of how small we all are and how incredibly beautiful the world is.”

Pixie Geldof, model, musician and activist

Ironically, too, given that it is now so much easier to see, enjoy and learn about nature both on our doorstep and in parts of the world that were once only accessible to the most intrepid scientists and explorers, we also seem less at one with nature than ever before. My own interaction with nature feels confusing and unsatisfactory. I know I need it for my physical and mental wellbeing. I get cabin fever and often crave to be outside. I am overawed and sometimes intimidated by nature’s power while recognising its vulnerability, and the jeopardy in which our way of life and rapidly expanding population are placing it. I am trying to reduce my personal impact on the planet, but I am not a natural campaigner. I live in a leafy London suburb with allotments nearby. I like hearing my neighbour’s cockerel – it reminds me of “real” nature – but essentially I am now an urban creature.

I grew up in a textile-producing area in the West Riding of Yorkshire and am old enough to remember the industrial pollution in the valleys, which contrasted starkly with the fields and wooded hillsides that rose up to merge with the moors. Both landscapes were part of my daily life. My brothers and I roamed the countryside, nature walks were my favourite school lesson and vegetables came from the garden. Shopping took us down the hill to the local town. We were proud of the mills and cloth produced in the area and wanted the industry to flourish. We accepted the sooty air, waste heaps, polluted rivers and smoke- blackened environment as a corollary of employment and a reasonably flourishing local economy. Not, though, a necessary corollary. The second Clean Air Act of 1968, which drove real change, was a reason for celebration.

Photographed by Kristin J Mosher

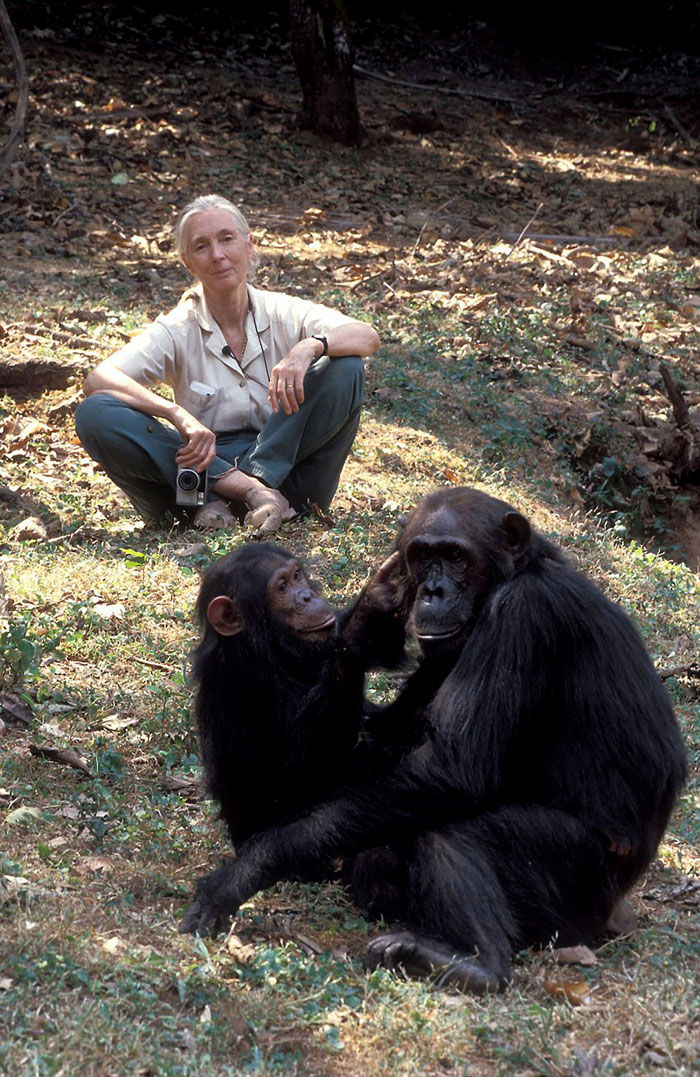

“Indigenous peoples around the world have always known how to live in harmony with their environment and all its inhabitants, but many of us have lost this wisdom. We are all connected. Every day the choices we make impact our world. It is up to each one of us to ensure that we make the right choices for the benefit of all earth’s inhabitants.” Jane Goodall, primatologist and anthropologist

As a fashion historian, I have always been interested in the business of fashion and recently, with my increasing involvement in debates around sustainability, I have often thought of my childhood. Today in Britain, we have effective environmental laws, which we must maintain, update and enforce, but millions of people in the global south now experience what I witnessed as a child on a massively increased scale. Fashion also has a profound social impact, with labour abuses particularly prevalent in factories supplying the cheap fast-fashion industry.

It has taken at least four decades of increasingly vocal campaigning to get recognition of the devastating environmental damage caused by the fashion industry. Forecast to rise at an alarming rate, it is now an issue of international concern at the highest level and the wider industry is starting to wake up. Science, technology and business have a big role to play in radically reducing the industry’s reliance on non-renewable, scarce and virgin natural resources, developing innovative ways to use waste and designing circular manufacturing systems. The problem, however, encompasses more than materials and manufacturing. It is also about over-production, the structure of the fast-fashion model with its accelerated cycle of drops and over- consumption. As consumers, we have a role to play. We can be active, exercise choice and make demands. There are alternatives to buying new: we can buy vintage and secondhand or rent, share, swap and pass on our clothes. Whatever we acquire should have value for us and a future in our wardrobes until it is responsibly recycled. Clothes to wear and chuck are a nonsense that we, and our planet, cannot afford.

Self-portrait by Tali Lennox

“I spent a lot of my childhood on the Balearic islands, so much of who I am comes from the mountains and forests of that place.

I feel as if I belong when I hear the sounds of birds and trees on the wind. A lot of my work is about a yearning for times long since past and the struggle between illusion and reality. In this painting, I depicted myself almost as an AI robot; the natural scene in the background is shown as merely a facade, like a backdrop in a theatre. So many of us, myself included, have forgotten its source and profound harmony with nature. We have all been thoughtless and blindsided by the products we consume and depend on, and need to change our frame of minds and our choices. What’s important, though, is to have the curiosity and openness to educate oneself on how to treat the planet with more awareness and positive intentions.”

Tali Lennox, artist

We can also look for fabrics whose production has a lighter impact on the environment and those with a resonance for us as individuals. Materials that reassure and give pleasure will get more use and better care, such as linen, which becomes softer with washing and wear. It may crease but it has character and robust durability. Linen, particularly certified organic linen, is a wise environmental choice. Grown in the right climate, flax needs no irrigation and even conventionally farmed crops require few pesticides and herbicides. Organic cotton is far better for the health of the land than conventional cotton, but it is still an extremely thirsty crop and a luxury rather than a staple. Cotton with the Global Organic Textile Standard certification carries the added guarantee that it has met the organisation’s ecological and social criteria throughout the supply chain from harvesting to labelling. There are many certification schemes – too many for the layman to understand their nuances, but they play an important role in the armoury of ethical designers. I now look for viscose and lyocell certified by Canopy and the Forest Stewardship Council, which ensure that the fibres come from sustainably managed forests. If we are to continue to use viscose, we need these schemes, and branded fabrics like Lenzing’s Tencel and Ecovero, to protect the world’s ancient and endangered forests from being destroyed.

Many of us happily wear recycled clothes but we are suspicious of fibres created from recycled textiles.

Wool has been recycled for woven fabrics (and home knitting) since the 19th century. High- quality recycled cashmere made from factory waste is a recent innovation. We regularly celebrate fabrics made from recycled plastic. Recycling nylon and polyester also reduces waste and the laundry bags designed to contain the microplastics they shed during washing are sensibly large.

Photographed by Angelo Dominic Sesto

“I think it is important to protect ourselves and the planet, more now than ever. In addition to the provable information highlighting the serious issues and risks we face, there is also as much, if not more, misinformation regarding the natural world and the alleged effect of some of our contributions. Most of which simply isn’t true. and is in fact putting this planet and its inhabitants at an even higher risk of extinction than it has ever seen.” Wilson Oryema, artist

I would be the first to admit that there are too many clothes in my wardrobe and fabrics that I should avoid. I try to rationalise my choices, and buy selectively, but fashion’s supply chains are complex and obscure and it’s often a garment’s colour, pattern or style that catches my eye and imagination. Garment labels are woefully inadequate, though a few companies have admirable websites with clear information about fabrics and trimmings and factory locations. Blockchain goes a stage further, enabling customers to scan and discover a garment’s history. Perhaps because of its novelty, or my innate curiosity, blockchain excites me. It inspires trust and builds rapport between purchaser and designer, and potentially with the product and those who made it. Ultimately everything in our wardrobes comes from nature. Unlike 21st- century humans, nature is never wasteful. If we want a sustainable future, we need to follow nature’s example.

Photographed by Colin Dodgson

“There’s nothing more beautiful, terrifying, calm, violent, chaotic and serene than Mother Nature. Coming face to face with one of my biggest fears, (a great white shark) very near to where I used to surf three times a day, keeps me humble and connected to what really matters in life.” Colin Dodgson, photographer

Self-portrait by Vivien Solari

“I swim in the cold sea to connect with nature and the elements, to see the changing of the seasons.

It allows me to escape for a short while from the fast pace of life, reset and gain perspective. The experience of being in cold water brings you into the present moment. We are nature, but we have become disconnected and are forgetting that we are part of it. Modern advances and technology are very important to us; humans are amazingly creative and innovative, but we owe a lot of these advances to resources found in nature. The disconnection makes it easier to carry on taking without thinking of the consequences. Reconnecting is important for our health and our soul, and we are more likely to care and protect our natural world.” Vivien Solari, model

Photographed by Justin Bastien

“My childhood summers were spent on a small island in the Muskokas surrounded by deep, cold Canadian waters. The rustic cottage was built by my great-grandfather and had no electricity or indoor plumbing. The sun lit our days and our nights were illuminated by the glow of kerosene lanterns and candlelight. Each night I fell asleep listening to the haunting calls of loons echoing across the lake and the sound of wood sparking in the fireplace while elders murmured and rocked in ancient creaking chairs by the crackling fire. By day, like an animal, I roamed free, naked, bare feet racing along the paths that deer made in the dappled birch forest. It was here, in this sacred space of nature, that I learned to commune with sound and silence and space. It was here that my small child self delighted that ‘tree’ rhymed with ‘me’ and that if you spelled ‘dog’ backwards it was ‘God.’ It was here I learned to be human. It was here I learned to be me. In Latin, ‘humus’ means ground. Quite literally our connection to the earth is the foundation upon which our ‘human beingness’ depends. Let us always remember and act as such.” Shalom Harlow, model

Edie Campbell, model. Photographed by Alasdair McLellan.