We are living in a material world, and all of us are material people. Historians and archaeologists track human development by the material that defines each period of human history – the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age. Since the dawn of the industrial age, our consumerist habits, manufacturing practices and synthetic fibres have catapulted the planet into the era known as the anthropocene. This epoch is defined by humanity’s mass impact on our natural world. Global trade, mass media and standardised goods have created a modern culture with an insatiable and unsustainable obsession for newness.

My own obsession with novelty dovetailed with a growing tedium about the fashion industry and its wasteful practices. The fantasy of fashion had become like a laundrette, with the same ideas, the same designs, the same materials spinning over and over again, ever quicker. It was in this state of mind that I discovered the fundamentally different approach of biodesign. By integrating design with biological systems such as plants and bacteria, it could lead to the creation of holistic products for a more sustainable future. Already, “spider silks” are being spun from modified yeast by Bolt Threads, and Modern Meadows is harvesting lab-grown collagen to create buttery leathery materials. Even the humble by-products of pineapple harvesting find a new life with Piñatex, which spins the leaves of the fruit into textile fibres.

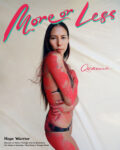

Jess wears Piero D’Angelo’s speculative garment harnessing the potentials of lichen

As an emerging discipline, biodesign offers the potential for infinite new designs, with a variety of sources for aesthetic ingenuity. The design technologist Nicole Stjernswärd’s inspiration for her colour dye system came from a fascination for the way Renaissance painters depicted light. “I ended up behind the scenes at the chemistry lab at the National Gallery and Dr David Peggie showed me the analytical tools that they use to take small samples of old paintings,” she explains. Through this, she learnt how the Old Masters mixed paints using local and natural resources; the contrast between them and the chemical paints now found in art stores is obvious. “We have largely forgotten how to make colour for ourselves,” Stjernswärd says. This interaction led her to develop the Kaiku system, creating colours using plant waste as a sustainable alternative to synthetic pigments.

Collaboration is the backbone of biodesign. Designers work together with living materials to create new ways of consuming and producing.

Collaboration is the backbone of biodesign. It is about designers working together with living materials to create not only sustainable products, but also new ways of consuming and producing. The collision of ideas within biodesign comes not only from scientists and designers, but also from philosophers and environmentalists. For Zowie Broach, head of the fashion programme at the Royal College of Art, ethics must become a natural part of every design process – “bio” or otherwise. “We have to be elegant as designers,” Broach remarks, “by understanding our times, and facing the future positions we will hold.” This is the reason why speakers such as Ionat Zurr, Oron Catts or Daisy

Ginsberg play an important role by asking ethical questions surrounding biodesign in a way that can be understood not only by those working within the industry but by the general public too.

Speculation and the time to experiment have both been eroded by the hyper speeds of modern consumerism. Yet for biodesign to flourish, there has to be more investment in research and development – it is not as simple as replacing one material with another. The biodesign hub Open Cell, founded by Thomas Meany and Helen Steiner, has been created to give scientists and designers the space to play out collaborative efforts. Adjacent to Shepherd’s Bush Market, Open Cell is a labyrinth of former shipping containers converted into transparent labs, breezy studios and workshop spaces. Piero D’Angelo, who has a background in womenswear and textiles, is one of the designers in residence. D’Angelo’s ongoing project is an exploration of the potential of lichens to the garment industry. Often found on tree branches, lichens are a symbiosis of fungus and algae – and, he discovered, also absorb pollution. “Imagine in the future if your clothes absorbed toxins in the air around you,” he says. Although it would take years to grow enough lichens to make one garment, “I think we forget just how important speculative design is,” D’Angelo says. “It is the middle step between expanding knowledge on current design and the final envisioned product.

“If the fashion industry wants to effect real change, it needs to adapt to the natural world, which doesn’t work on a timescale of six collections a year,” he continues. “Wildlife is breaking down, being forced to adapt to our current industrial practices.” There is an irony to our obsession with novelty, in that we are quick to demand new products, but slow to adapt to new ways of thinking. Imagine what would happen if we took a step back into nature, and adopted a more conscious approach to living. There would be more time to cherish the natural materials we have – but could very soon lose.