At a time when the world is upside down and many of us are drawing more deeply on our internal resources, “transportive magic” might be just what we need to inspire our creative salvation.

At a time when the world is upside down and many of us are drawing more deeply on our internal resources, “transportive magic” might be just what we need to inspire our creative salvation.

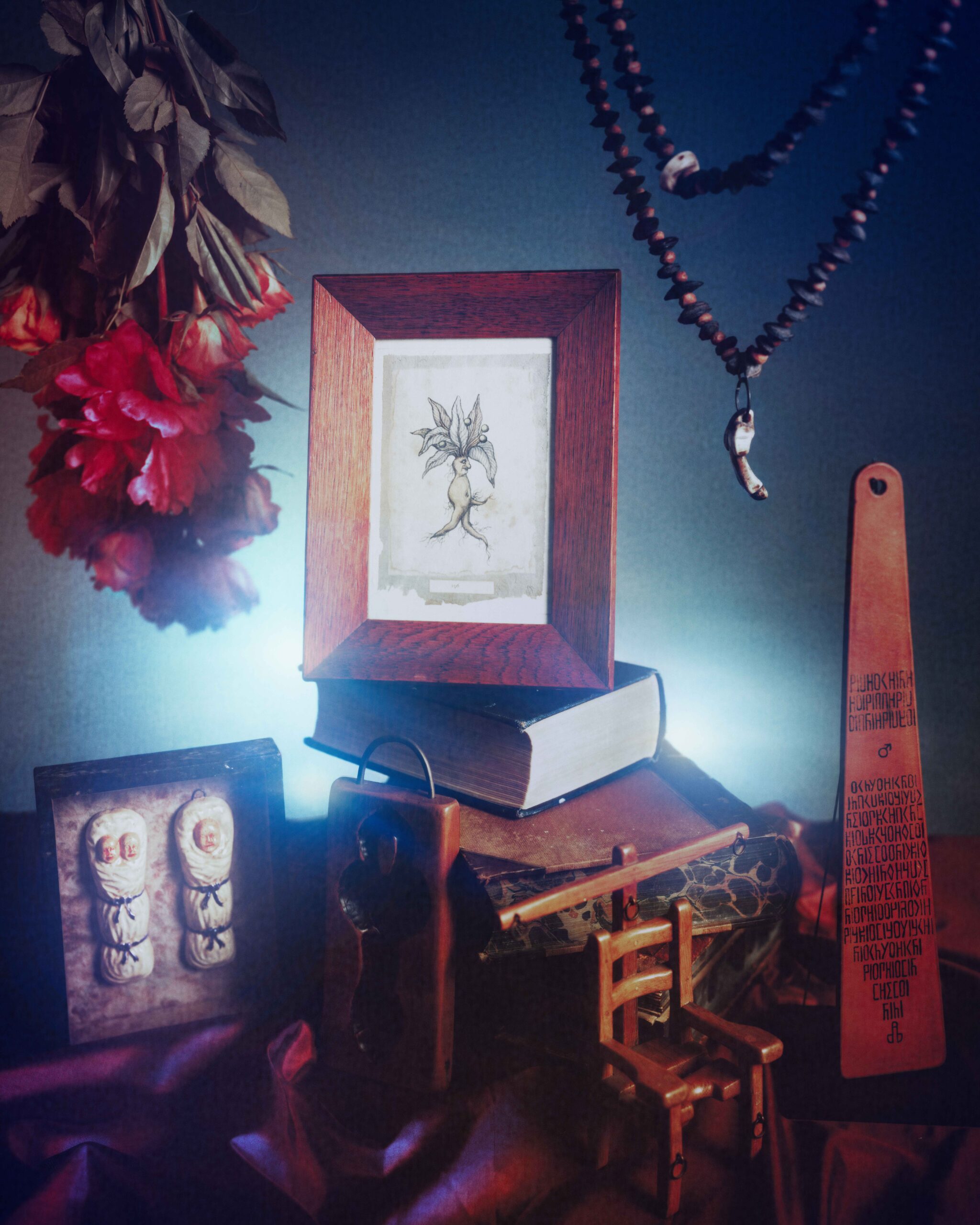

Begun by JHW Eldermans and continued by Bob Richel, from whom the collection passed to the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in 2000, the Richel-Eldermans Collection occupies a hinterworldly crossroads all of its own. One with directions towards sex magic, traditional witchcraft and angelic conjuration, with illustrative styles which suggest for some viewers possible masonic leanings. Comprising hundreds of occult images and objects, it documents over a century of archival references from hermetic magical orders and ritual objects from the combined practice of European magicians and occultists.

Part of the institution’s DNA is its role as a locus of study, its roots going as far back as the 1930s when its founder, Cecil Williamson, formed the Witchcraft Research Centre, following a request from the Foreign Office to assist with its enquiries into the occult practices of the Third Reich. And though it may not be the first museum with an abundance of magical objects in its collection – that was probably the Priestess and Princess Ennigaldi’s Museum in Ur 2,500 years ago – it is certainly the world’s largest publicly accessible collection in existence today. Exploring magical practice, the current museum draws comparisons with other systems of belief from ancient times to the present day.

When a postwar return to his original career in film production seemed an unlikely prospect, Williamson forged a new path. Building on his research, he opened a museum at the Witches Mill in Castletown on the Isle of Man in association with Gerald Gardner – a founding father of Modern Wicca. In later years, he was involved in the formation of three other museums of occult objects, including one at Bourton-on-the-Water which was firebombed during an intensive period of intimidation. Following this, Cecil relocated to Boscastle, Cornwall, where the current museum has been situated since 1960, having found its spiritual home.

“The British public likes to think that there are witches to be found in remote places, for they know it still goes on, but have no wish to be involved in any such goings on”

Considering the public’s attitude towards the museum and its focus of attention, Williamson said, “the British public likes to think that there are witches to be found in remote places, for they know it still goes on, but have no wish to be involved in any such goings on. Bless them.”

It is a place of pilgrimage and place for study for many, housing a unique collection of magical objects and a sizeable occult library and archive. But what can we learn from these collections now? At a time when we have never seemed more divided and our societies less stable, can witchcraft save the world? As the current custodians of the museum’s remarkable collection, we sit between the many worlds of many others – we don’t need to have an intimate understanding of them all but require a sympathy and respect for all of them. To listen is key.

As Cecil Williamson himself said, “those who work witchcraft are on the whole a divided lot… the golden rule for the museum is to love them all sincerely, to listen carefully, but never to become involved.”

Having defied description since its creation, the Richel Eldermans Collection may be impossible to explain, just as its creators desired. The largest visual record of it so far published is a muter libris or wordless book. Ruth Hogben’s images shown here were created for the museum using a singular photographic process, an alchemic wonder of its own, situating these objects within the parallel continuum the museum as custodian provides. Without interrogating them, it allows a conversation without words to develop with the audience.

We are privileged to work amidst great mysteries that are continuing to unfold. We would like to finish with a favourite saying of the primary creator of the subjects of these photographs, with which we are more than content. “The more you know, the more you realise you don’t know” – JHW Eldermans

Please purchase our print edition here