Odds are you’ve come across at least one fantastical sartorial creation from Julie Schafler Dale’s seminal book Art to Wear—if not on your own bookshelf, then enduring on your Instagram feed. Beginning in the 1960s and spanning decades, the wearable-art movement sought to express through clothing what was traditionally reserved for the gallery wall. Time-honoured craft techniques were pushed out of their contextual comfort zone and into the changing world around them. A prominent fixture in the movement since its inception, Jean Cacicedo is known for her elaborate crocheted, dyed and pieced-together coats, using techniques developed over the last five decades. With the current fashion infrastructure in crisis, it’s perhaps more relevant than ever to look to her lifelong career of making clothing unconcerned by runway calendar restraints or fickle trends.

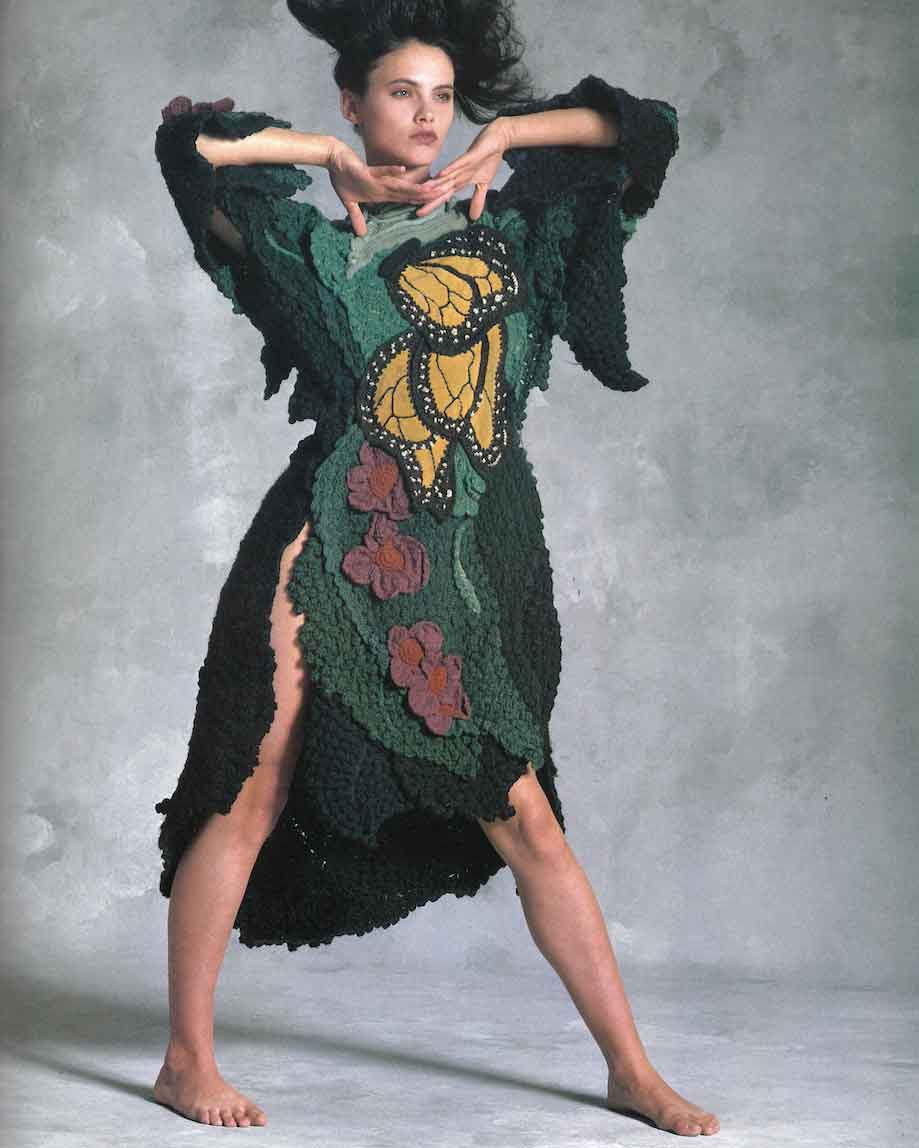

Jean Cacicedo, “Transformations”, 1977

What does Art to Wear mean to you? What led you to work with your chosen techniques?

The term Art to Wear was established in the 1980s to describe an approach to clothing wherein the core value is the celebration of the handmade crafted object. It transforms the body and the spirit, both physically and metaphorically. My intention has always been to fashion the body – not to make something necessarily fashionable. As a sculpture major at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn during the counter culture revolution of the 1970s, I explored the technique of crochet because I saw the creative potential in how a single point in space could make lines, shapes and forms. Crochet was primarily viewed, as was most textile art during that time, as women’s work. I was never concerned with the definitions and biased attitudes towards handiwork. I wanted to make art that could be worn and seen in the streets, not just in museums and galleries. Curiosity about various processes led me to adapt some of them into my own practice… and yes, it was all by hand and very, very time-consuming. Without craft, however, there would have been no art. I may start with a vision or concept but the process has ways of evolving from the original and I find listening to my materials to be of great importance.

You were carried at the legendary San Francisco shop Obiko. Why was that boutique in particular so influential?

I have always been disciplined when it comes to making my art. I love working problems out with materials and I have never once counted the hours it takes to make a piece. I moved to Berkeley in the Bay Area in 1980 and was introduced to Sandra Sakata of Obiko. With Sandra’s encouragement, I began creating a small production of one-of-a-kind of dresses and vests. As sales grew in the 1980s and 1990s, it was clear that there was enough interest to support these limited editions. San Francisco was a happening place, culturally and artistically; the style of dress here matched our style of living and connected us as designers to its cultural identity. Producing these pieces was a challenge for me, but a necessity at the time, and I grew to love working in multiples. Obiko was a great place to sell on the West Coast. I continued to make one-of-a-kind artwear, selling them at Julie: Artisans’ Gallery on Madison Avenue in New York. The founder of the gallery, Julie Schafler Dale, wrote the first major book on the subject and was very helpful in exposing many artists working in wearables and publicising the wide spectrum of the “Artwear” movement nationally.

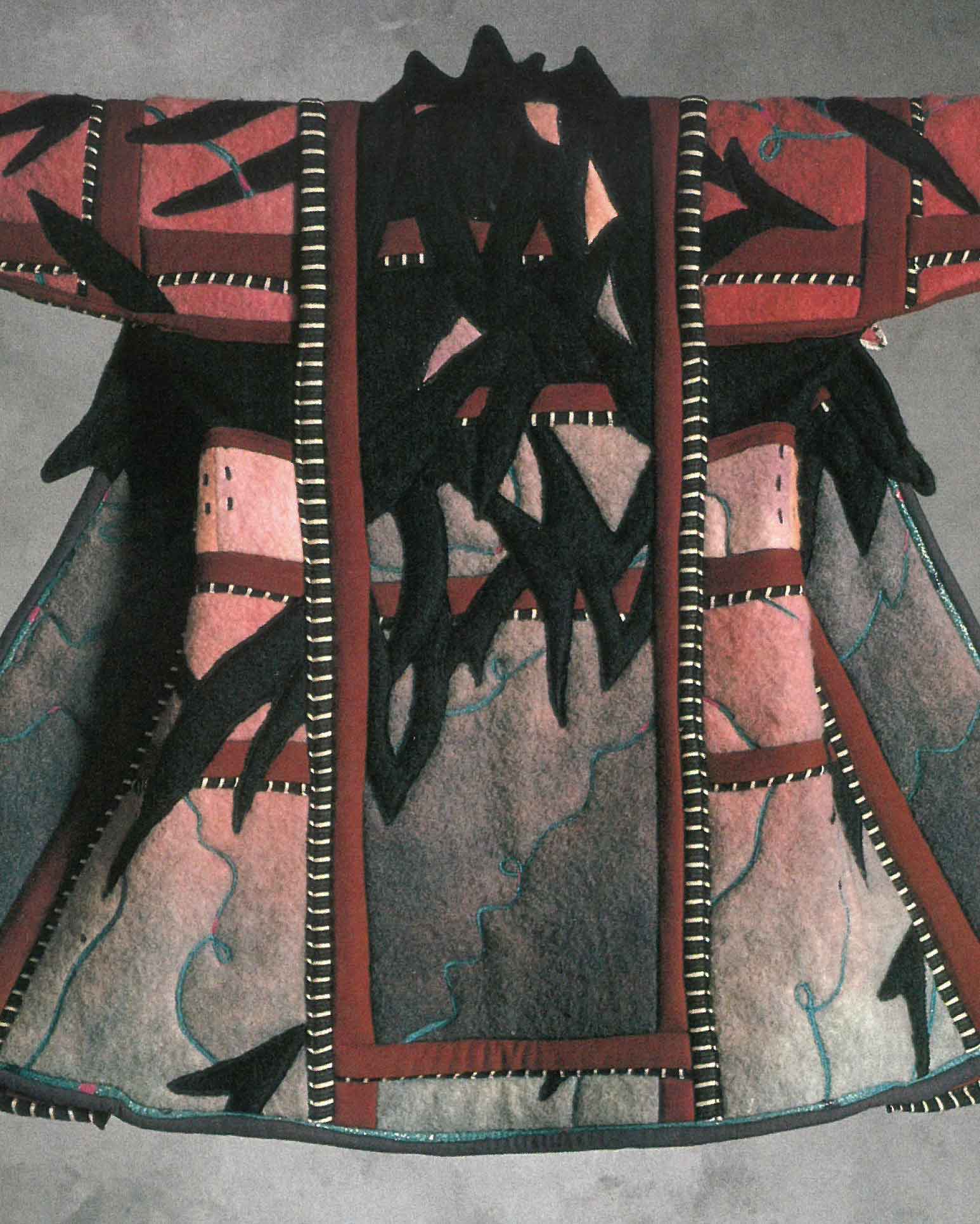

Jean Cacicedo, “Cactus Coat”, 1978

Jean Cacicedo, “Black Leaves”, 1981

You’ve spoken about the role of spirituality in your work – how has that evolved over time?

I’ve always considered myself a spiritual being, but it was not necessarily a path someone taught me. I have a strong sense of belonging and gratitude to all life around me and feel that spirit within when I am creating my art. Making art enables me to tell my stories visually. There are days when I have nothing to express but when I am moved, it is because my soul and mind have been connected. It’s a bit abstract to explain, but I would have no art if it weren’t for this connection.

It is clear that the clothing industry is buckling under the weight of the fast-fashion model with the concerns around mass consumption, sustainable manufacturing and individual economic stress that come with it. What does this mean to your practice?

I truly think some consumers will tire of the ready-made and invest their time and energy in creating for themselves or buying respectfully produced products. The DIY movement is just an example of a trend towards traditional crafting techniques. I hope we in developed countries can steer our industry away from the preoccupation with faster production and ever lower price points. Just like our organic slow-food movement has been creating momentum, hopefully so will the garment industry take a similar path. If we can learn from tradition, we can also learn to be innovative.

Jean Cacicedo, “Chaps: A Cowboy Dedication”, 1983. All images taken by Otto Stupakoff. Copyright Julie Schafler Dale ‘Art to Wear’, Abbeville Press

Please purchase our print edition here